The Obvious Business Case for Sustainability

Sandvik is a global engineering group specializing in the manufacture of tooling systems for advanced industrial metal cutting, mining equipment, construction equipment, advanced stainless steels, and special alloys. The company also has a deep history of social responsibility.

We spoke to Mats W. Lundberg, Head of Sustainability, about the group’s ambitious sustainability goals and how, in his opinion, any organization can make the shift to a circular economy.

Let’s start at the very beginning. How does a multinational engineering company begin to think about circularity?

Well, at least when I think about circularity, it's about business possibilities. When you talk about sustainability in general, you need to put business front and center. Because what is the purpose of sustainability? It's to make money, save money, reduce risk and have a positive impact on the environment. That’s the big scope of what you are trying to do.

You might start by looking at risk and raw materials, for example. Depending on your industry, there can be a limited number of suppliers and there’s a variance between the levels of quality control in different countries. Your suppliers may pose a risk to the core values or even the reputation of your own company, so you sometimes must handle and mitigate risk.

One way to do so can be to make suppliers sign and comply with codes of conduct. But it’s not always a perfect scenario. One benefit of introducing circularity is that you replace virgin raw material with circular material by recycling from products that have already been in use. Then you become less dependent on a risk associated area.

Let’s take it another step. Suppose I sell a mining machine or metal tube to a customer, but I also offer to buy that product back when it has reached end-of-life. From a customer point of view, the product has become scrap at its end of life, but instead of selling it to a scrap dealer they can be incentivized to sell directly back to Sandvik. The material can then be reused as raw material once again.

To be able to buy back a used product from a customer is also an advantage for Sandvik as we know the exact content and chemistry, maybe even the batch number, of our own products. Instead of random scrap, we can use those tubes in a new melt and know that we already have almost the exact composition for what we want to produce. You need a small amount of virgin material at the very top to calibrate the perfect mix - in the same way you might add a little salt and milk to a shake-and-bake bread mix to get the taste right.

At Sandvik, we call this secondary raw material, not scrap. Secondary raw material is also less expensive than virgin raw material and it has a smaller environmental footprint. This is a benefit for both Sandvik and our customers. By designing a closed loop system together, we help customers handle scrap, and with less demand for virgin raw material the environmental impact is smaller.

From a financial perspective, a closed loop system like this is helping us to save money on raw materials and mitigate risk at the same time as we are increasing sustainability. In short, a perfect example of how circularity is also beneficial for business. This is an example that can be used as a guide to start thinking in new and more circular ways to find other business cooperations or product lines where a similar approach could work.

You present circularity with such a strong business case. Why would an organization not already be pursuing it as a sustainability goal?

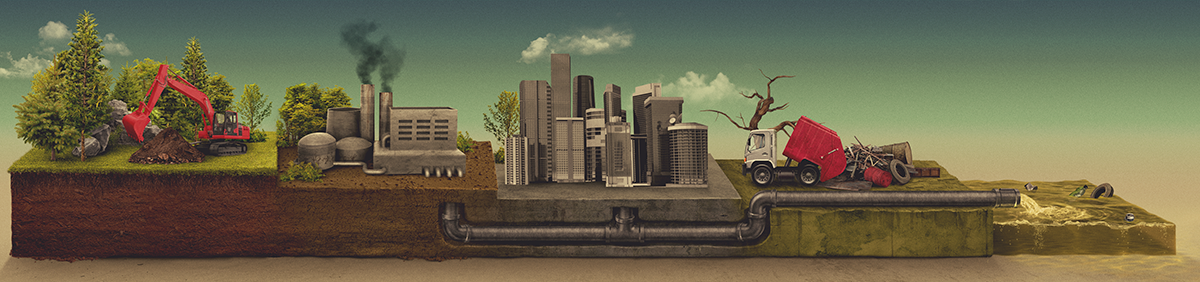

The problem is that the traditional linear economy is built on multiple transactions. You look at whether your inputs are expensive on one end and calculate your earnings at the point of sale on the other. But when you’re building a circular economy, you’re figuratively bending that straight line so that the two ends meet, suddenly your raw materials buyer and the sales teams will start to cooperate because one needs to buy product back from the other.

It has to be a transition, so that’s why we call our sustainability strategy, ‘make the sustainability shift’. The infrastructure needs to be implemented, production facilities might need to be adapted and business models redesigned.

There’s also a mental shift away from 150 years of a linear economy, so you can’t transform an entire company in one go, it will probably take 10 or more years of iteration to get everything in place. That’s why it’s important to realize there is a business case, we’re not doing sustainability only to tackle climate change, it’s about both.

Circularity works when you build the business case. Some raw materials, like plastic, are too cheap to implement a buy-back. That’s a limitation, but steel is an expensive raw material, so circularity makes a lot of sense for us in mining and steel manufacturing.

The more circular you get, the more savings you will realize because you might have missed some possibilities before moving to a new business model. If I have a tube, why should I sell it? Why shouldn't you rent the tube instead?

What happens if you go over to the ‘rent instead of sell’ mode?

Well, then I would like to develop sustainable tubes that never break, because I want you to rent it forever, right? From a sustainability point of view, that is great because then less material is out in circulation. That's great for the environment and from a business point of view, I get paid every month.

Your product might become more expensive to make, but now it’s designed for ‘forever’ use and guarantees you a monthly income. When the customer no longer needs it, we get our raw material back and can use it to produce a new product.

It takes thinking outside of the linear box that we’ve been locked into. Ultimately the circular economy is what we did before money: we traded, repaired and reused.

Extreme linear supply chains only arrived because things became so cheap to manufacture. There isn’t the same financial pressure to be resourceful with consumption when you can throw things away. But now we’re realizing the business benefits of the circular economy; high resourcefulness is back on the table.

Convinced by the business case, and knowing that change could take a decade, what can you do in the first year to move in the direction of circularity?

Five years ago, I started to look at: where is it easiest to change? Don’t fight against impossible odds with the grand notion that everything should be circular overnight. Instead, go where you can build the business case.

Forcing sustainability on people will only make the organization frustrated, then you’ve lost hope of gaining momentum. Despite Sandvik being a business-to-business company, the first thing I did was to look at our products closest to the consumer market.

Sandvik is manufacturing strip steel that our customers are then using to produce kitchen knives and razor blades, for example. Consumer research concluded that, on average, women are the main purchasers of household goods in Europe. Women were also more likely to buy an ecological product. Then you see an opportunity to brand a ‘green’ razor blade or ‘eco’ kitchen knife as it will be appealing to your customer.

The opportunity to collaborate with the manufacturers and repackage the same product by adding sustainability as ‘value’ improves their product portfolio. By also offering to buy back the strip steel that is otherwise scrapped when they’re making these razors or knives, gives them double points — green steel and a circular economy.

With a good business case, you’re no longer just the person who’s preaching about the environment. I’m not telling you that the world is burning, I’m telling you how to make more money and tackle climate change.

Then you’re opening people’s minds to it in a positive way and that will influence decision makers in other departments to also look for those simple entry points.

When you talk about business-to-business, how do you convince a mining machine customer to think about circularity?

First, I would make sure that we're not talking about surface mining, we're talking about the underground, because that is where you have the interesting business case to begin with.

If you go with a battery powered electric vehicle instead of a combustion engine, you generate less emissions in the mine. Lower emissions require less ventilation, so it’s cheaper to run an electric powered mine than a diesel one — and the deeper you get, the more ventilation costs you’re now saving. Switching to electric also reduces the carbon footprint of the ore you are extracting. So in selling the idea of an electric mining machine, you also get the customer thinking about how they will brand their new, greener ore.

Metals and minerals power mobile phones, so you get the mining company talking to a manufacturer who wants to market phones with a lower carbon footprint, because your raw material is now extracted using less CO2 and less water.

You help your customer to connect the dots and find a toolkit for driving a higher price from what they are manufacturing, based on the new added value passed on to their own customers.

And this works, companies are buying green steel at a higher price because they recognize the added value and consumer demand. From a consumer perspective, it's empowering to buy and use environmentally friendly products. People are buying organic bananas, why wouldn’t they also buy an organic Volvo? The difference in price between a green steel car and its regular model is negligible, so it works financially and morally for the customer.

You have stated that Sandvik wants to be 90% circular by 2030. What impact will 90% circularity have?

Many people misunderstand the circular economy as using less material. It’s actually about being more responsible and not wasting material that is in circulation. You could build bigger machines, but when it comes to end of life you have to take care of and reuse the materials.

I use the Swedish phrase, “resurssnål”, which can translate to being stingy with your resources, mindful of how you use them and avoiding waste.

Throwing things away is too passive and ignores the reality that waste ends up in a physical place, it doesn’t disappear from the planet. Circularity uses materials in a more mindful way, reduces landfill and shows responsibility.

For our part at Sandvik, I think by signaling that we want to be 90% circular by 2030 sends a strong message. We want to achieve a change, which means our suppliers need to think differently, our customers need to think differently and certainly, most of all, we need to think differently.

The upside of our ambitious target is phenomenal from an economical point of view, we’re talking hundreds of millions if you do this right. Then from an environmental point of view, everything you do right in circularity contributes to tackling climate change. The two are in symbiosis.

And that’s sort of it really. Sandvik’s purpose is ‘We make the shift — advancing the world through engineering’. From my point of view, it’s quite difficult to advance the world without making it more sustainable.