Get value for life: Proper bolt securing may reduce costs 1,000 times

While there may be cheaper alternatives, choosing the right bolting solution will pay you back many times over in the long term. Here we take a look at the importance of life cycle costs (LCC) in bolting.

It is a question that many an engineer or project manager has been faced with: whether to take the cheaper short-term option now and worry later about the consequences of machine failure; or to invest more from the outset in quality components, but wait years to see a return on investment in terms of lower cost of ownership. Increasingly, companies are seeing the benefits of the latter approach, a concept known as life cycle cost (LCC), which is defined as the total cost, from acquisition to disposal, of operating a machine or plant. But still many fail to recognise the economic advantages of taking the long-term view – not least when it comes to bolting.

It is a question that many an engineer or project manager has been faced with: whether to take the cheaper short-term option now and worry later about the consequences of machine failure; or to invest more from the outset in quality components, but wait years to see a return on investment in terms of lower cost of ownership. Increasingly, companies are seeing the benefits of the latter approach, a concept known as life cycle cost (LCC), which is defined as the total cost, from acquisition to disposal, of operating a machine or plant. But still many fail to recognise the economic advantages of taking the long-term view – not least when it comes to bolting.

“The concept of LCC is not well practiced in many organisations because they are driven by short-sightedness and a focus on short-term cost reduction instead of a focus on what drives cost,” says Christer Idhammar, founder and CEO of Raleigh, North Carolina-based maintenance management consultants Idcon Inc. “The right equipment might cost more, but the cost of ownership is lower. Long term you will have much lower costs and better maintainability, and therefore higher reliability.”

Statistics show that more than 50% of accidents and failures in industries are related to bolt failures, and Idhammar has come across numerous such examples in his work advising companies around the world. In one extreme case, where a bolt came loose and fell into the machinery at a paper mill, a granite roll worth over $1million was destroyed and the plant put temporarily out of action. Investing in a better bolt securing solution at an early stage could have saved such a massive expense years down the line.

Siemens Industrial Turbomachinery, based in Finspång, Sweden, employs the LCC approach in its manufacture of gas turbines for power generation. Several years ago the company conducted a study of its assembly process and concluded that securing the roughly 2,000 bolts on each of its multi-million euro turbines was consuming too much time and causing too many injuries among its workforce. The method that was used to lock the bolts was a washer that was manually deformed with a hammer and tongs, a so called tab washer.

By taking a cradle-to-grave view on the bolt securing solutions it uses, Siemens has reduced costs throughout the lifespan of its turbines, and at the same time reduced workplace injuries and the costs associated with them. “Changing from the old method to Nord-Lock washers meant huge savings in time, injuries and money,” says Martin Lindbäck, Head of Project Office at Siemens’ R&D department. “We save about 50,000 to 100,000 Swedish kronor (5,500 to 11,000 euros) per gas turbine during assembly. And as we have to disassemble the turbine for servicing about four or five times during its life and unlock a lot of bolts and washers, there is a huge saving on maintenance costs during that life cycle. Downtime is very important for our customers, so every hour we can save when the machine is stopped is very important.”

Deciding on and investing in the right equipment from the outset can prove to be thousands of times cheaper over the life cycle of a product, but is often steered by internal politics or accounting procedures. Idhammar explains that as a rule of thumb, when a project has reached the halfway stage time-wise, only about 5 to 8% of the total cost has been spent. “But by that stage you have made decisions that will lock in about 85% of the future life-cycle cost,” he says. “You have decided at that point on having just one pump, instead of one pump plus a backup; on having stainless steel piping instead of galvanised; on having a bolt-securing solution that doesn’t guarantee that bolts won’t come loose. These are crucial decisions.”

If, at that halfway stage, you want to make modifications, it will cost 100 times more than if you had thought of it from the beginning. “And if you start operating the equipment and discover five years later that you have a problem, it typically costs you 1,000 times more,” says Idhammar.

|

Siemens saves about 50,000 to 100,000 Swedish kronor (5,500 to 11,000 euros) per gas turbine during assembly.

|

|

Machine producing high-quality paper: 5,000 to 100,000 euros per hour, depending on size.

|

|

Gearbox in plastics factory: 90,000 euros for new gearbox, 330,000 euros in estimated lost production time. |

|

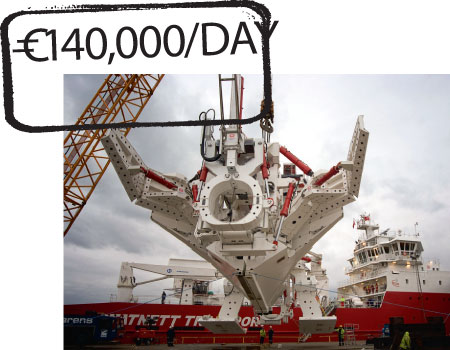

Ocean-going pipeline plough: 90,000 euros to 140,000 euros per day. |

|

Conveyors for transporting raw materials in mining applications: 87,000 euros per day. |