Superbolt® Multi-Jackbolt Tensioner Addresses Common Leakage Issues for Heat Exchanger Flange Bolting

With high-pressure equipment such as heat exchangers, flange leakage tends to top the list of things that could go wrong and have potentially profound consequences, particularly in the petrochemical and process industries.

This article is adapted from a white paper presented by Stephen J. Busalacchi, Superbolt Senior Product Specialist, presented at STATIC Arabia Conference and Exhibition in Al Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 13–15 May 2024. The full white paper is available for download on the Nord-Lock Group website.

With high-pressure equipment such as heat exchangers, flange leakage tends to top the list of things that could go wrong and have potentially profound consequences, particularly in the petrochemical and process industries. Leaks are always unwanted but nevertheless continue to occur, increasing the likelihood of lost productivity; safety and environmental hazards; and the risk of fires.

Inherent to their design and function, shell-and-tube heat exchangers (STHEs), for example, are under high pressure and can experience dramatic temperature and stress fluctuations. This places a tremendous stress on bolted flange connections, as flange joints are the primary sources of heat exchanger leaks.

Heat Exchanger Flange Joints and Leaks

STHEs and their variants are frequently used in petroleum and chemical processing plants because of their ability to cover the wide range of required process pressures and temperatures. Their primary function is to transfer heat energy across metal walls between hot and cold fluids. Tubes, tube sheets, and flanges (mostly girth type) are among the primary components exposed to wide temperature differences between the hot and cold fluids within heat exchangers.

Even with the best intentions, insufficient tightening and uneven bolt loads lead to flange leaks —especially as the flange connections and bolt sizes increase — with these larger bolts requiring much higher tightening torques. Higher torque levels also increase the likelihood of safety hazards due to problematic tightening methods and larger required tightening tools.

Thermal and Non-Thermal Leaks

Flange leakage is extremely common in petrochemical refineries, happening about every eight months on average. Installation and maintenance crews deal with two types of leaks:

- Thermal: Happen only during equipment start-up or shutdown due to the different rate of expansion and compression between the flange and bolt. They tend to stop automatically after temperature reaches equilibrium.

- Non-Thermal: Happen at any point in time, especially after long running hours or after shutdown due to the condition of the gasket, flange face, or stud bolt. The bolt tightening method could also be a root cause of this type of leak.

How Leaks are Traditionally Solved

Thermal leaks are traditionally solved by hot bolting. It requires a tech on standby to perform bolt retightening whenever a leak is detected. If the leak does not stop, then the gasket is changed out to provide a better seal. If the leak persists, however, it then needs to be sealed.

In addition to low bolt loads, thermal leaks are known for high temperatures in the shell and channel. These can lead to bolt relaxation and flange rotation and leakage. Such a scenario can result in the flange catching fire (which requires a steam quenching process to prevent further equipment damage), extended downtime, and possible loss of life.

Non-thermal leaks can be resolved in several ways. The first is by increasing the bolt’s torque value. If that does not settle the problem, then the gasket might need to be changed out due to it being compromised. But if a new gasket does not stop the leak, then flange facing might be required should the flange itself be compromised. Each leak-mitigation method requires downtime that comes with its own unique and unpredictable challenges.

One of the most common methods used to solve both thermal and non-thermal leaks is torquing. However, a major problem associated with traditional bolting tightening methods, such as torquing, is that as the diameter of the bolt increases, the amount of torque required to tighten it increases to the third power of the diameter. Because of this, the largest bolt size a person can typically tighten by hand is one inch. Therefore, many installers resort to heavy-duty, expensive, and difficult to handle devices such as pneumatic, hydraulic, or electric torquing tools, while others have used large and cumbersome torque multipliers.

Because the nut is directly torqued, there is friction between the nut-and-bolt thread as well as in the nut-to-flange interface, thus affecting preload accuracy. Direct torque methods also cause torsional stresses in the bolt which limit the level the bolt may be loaded. These reasons tend to cause flange designers to use higher-strength bolt materials and/or larger size bolting, amounting to higher initial costs.

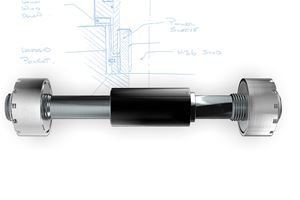

The Better Alternative: Superbolt Multi-Jackbolt Tensioners

Instead of tightening one large through bolt or fitted bolt, Superbolt Multi-Jackbolt Tensioners (MJTs) use several smaller jackbolts to drastically reduce the torque required to attain a certain preload. MJTs only require handheld tools, such as torque wrenches or air/electric impact tools, for installing or removing bolts from STHE flange joints. Since Superbolt MJTs were invented over 40 years ago, they have been a premium bolting method to installation and maintenance crews is various industrial segments.

For installation, the hardened thrust washer is placed over the bolt or stud, and the nut body is spun on by hand. The actual tension is achieved by tightening the small jackbolts. Similar to stretching, the bolt or stud is only tensioned axially. The nut body is tensioned at the same time as the bolt, so the bolt cannot spring back. Therefore, key advantages of MJTs are high safety against loss of preload and fast, simple installation and removal.

Calculated Cost-Savings of Using MJTs

Safety AspectsBecause MJTs require only small handheld torquing or air/electric impact tools, they are arguably the safest bolting method for tightening large diameter bolts/studs. The sledgehammer, however, is still the most dominant tool when attempting to bolt-up a piece of equipment. The brute force required in using it often leads to hand, arm, leg, face, and back injuries.

Installation/Removal Time ComparisonsThose unfamiliar with MJTs comment that it must take a long time to torque-up all the jackbolts. But in reality, MJTs have reduced installation times compared to other bolting methods. Adjustments to the preload can be made quickly by dialing in a new toque value and torquing the jackbolts to the new value.

Major time savings can be accomplished by using multiple workers to tighten several MJTs simultaneously. Since only handheld tools are used, the tooling required is easily obtainable and economical. Other time saves might not be obvious at first glance. For instance, it can sometimes take several shifts or even days to remove frozen bolts that often must be drilled or machined-out on site. Since MJTs tighten a bolt in pure tension, there is no galling or ripping of thread surfaces which can occur when applying a high torque to achieve bolt tension. Therefore, once the jackbolts are unloaded in an MJT, the nut body can be removed leaving the bolt as if it had been hand-tightened. The bolt can then be easily removed with nominal torque applied.

Elasticity and Reliability GainsIt is desirable for bolting systems to have as much elasticity as possible. Unlike conventional nut/bolt systems that do not compensate for thermal cycling and settlement, MJTs are highly effective in achieving additional elasticity, and commonly solve traditional high-temperature flange bolt loosening and leakage issues. This also means the ineffective and extreme danger of hot bolting of flange joints to deal with thermal distortions on start-up can be eliminated. Other attempts have been made to address the need for more elasticity, such as the use of disc spring washers and flexible gaskets; however, the benefit gains tend to be very modest and practically ineffective.

MJTs inherently have a spring effect since the load transfer is through the jackbolts and into the nut body, causing the main nut body to flex out slightly at the bottom and slightly at the top. This spring effect from the nut body and jackbolts not only adds elasticity to the main bolt but moves the load stresses away from the usual first few threads (as seen in ordinary nuts, which are rigid), and more evenly disperses the loading along the full thread engagement of the MJT and main bolt.

Reliability is enhanced with the added elasticity and the uniform preload capabilities. Flange integrity is highly improved and the risk of leakage can be significantly reduced.

Conclusion

Multi-jackbolt tensioners (MJTs) require only small handheld torquing or air impact tools to greatly simplify flange bolting with shell-and-tube heat exchangers (SHTEs). MJTs provide enhanced reliability through added elasticity and uniform preload capabilities. Not only do MJTs eliminate common leakage problems inadequately addressed by traditional bolting methods, they also enable considerable cost savings. Furthermore, cost savings are coupled with reducing expensive and unwanted downtime. Additionally, MJTs improve worker safety and reduce the time it takes to install and remove bolts.